Malcolm Engineer and the Wood on the Wheel

Once upon a time, there was a mouse called Malcolm Engineer. He lived in a small mouse house inside the great train house where the engines rested, and his job was to look after the trains and to mend them when they needed mending. There were human engineers too. They did all the big jobs. Malcolm Engineer mended all the small parts, the delicate parts, the difficult to get at parts that the humans, with their big bodies and their fat fingers, were too huge to do themselves. Sometimes he worked in the train house – and sometimes he worked on the trains themselves as they chuffed and rushed down the tracks.

One day, Malcolm Engineer was riding a train. He was sitting in a small room, a special room for a mouse engineer, with a cup of tea and a plate of cookies, checking through his tools and listening to the sound of the train as it chuffed and chugged down the tracks.

Chu-dun-de-dun,

chu-dun-de-dun,

chu-dun-de-doomf,

Crash, Bash,

Clatter, Smash.

The train lurched.

Malcolm’s tea sloshed in his cup, and the cookies slid off the plate and onto the floor.

Chu-dun-de-dun,

What was it! Malcolm leapt to his feet, grabbed his tool pack, strapped it on, and then he rushed up to the head of the train, up to the driver’s place.

The human engineer and the driver were talking, heads close together, shouting above the engine noise. Malcolm Engineer climbed close to listen.

. . . don’t know . . . something big . . .

. . . piece of tree or something . . . heard it crack . . .

. . . gone now? . . .

. . . leaves and things . . . sounds OK . . .

Malcolm climbed down again. There must have been a piece of tree, a branch, or something, lying on the track. Whatever it was, it was clear now – the train had knocked it off the track.

‘Still’ thought Malcolm, ‘I’d better check, better make sure it’s all, all right.’

Malcolm Engineer started walking down the train. He heard the human conductor talking to the passengers.

. . . don’t worry, Sir . . .

. . . on the line . . .

. . . all right now . . .

Malcolm opened a special door, a door he had made and fitted himself, and climbed down under the train. He could see the track and the sleepers whooshing and whizzing under his feet.

Under the train were the mouse-ways, the chains and ropes and pieces of metal that the mouse engineers used as their paths and walkways. They were wide and easy for a mouse to walk on – if the trains were safe and quiet in the train house – but this train was moving. It bumped and shook and jumped and rattled, and only a master engineer could walk these mouse-ways and not fall off.

Malcolm was a master.

He walked along, listening, looking, checking the train.

Everything looked good. Everything looked fine. Malcolm listened.

Chu-dun-de-dun.

Chu-dun-de-dun.

The train sounded just as it should.

Chu-dun-de-dun.

Chu-dun-de-dun.

But then he heard a different noise.

Chu-dun-de-screee.

Chu-dun-de-screee.

A human engineer, with human ears, would never notice – but a mouse’s ears are different – they can hear things that humans can’t.

Malcolm hurried up.

The noise got louder. Under the third carriage, from one of the wheels.

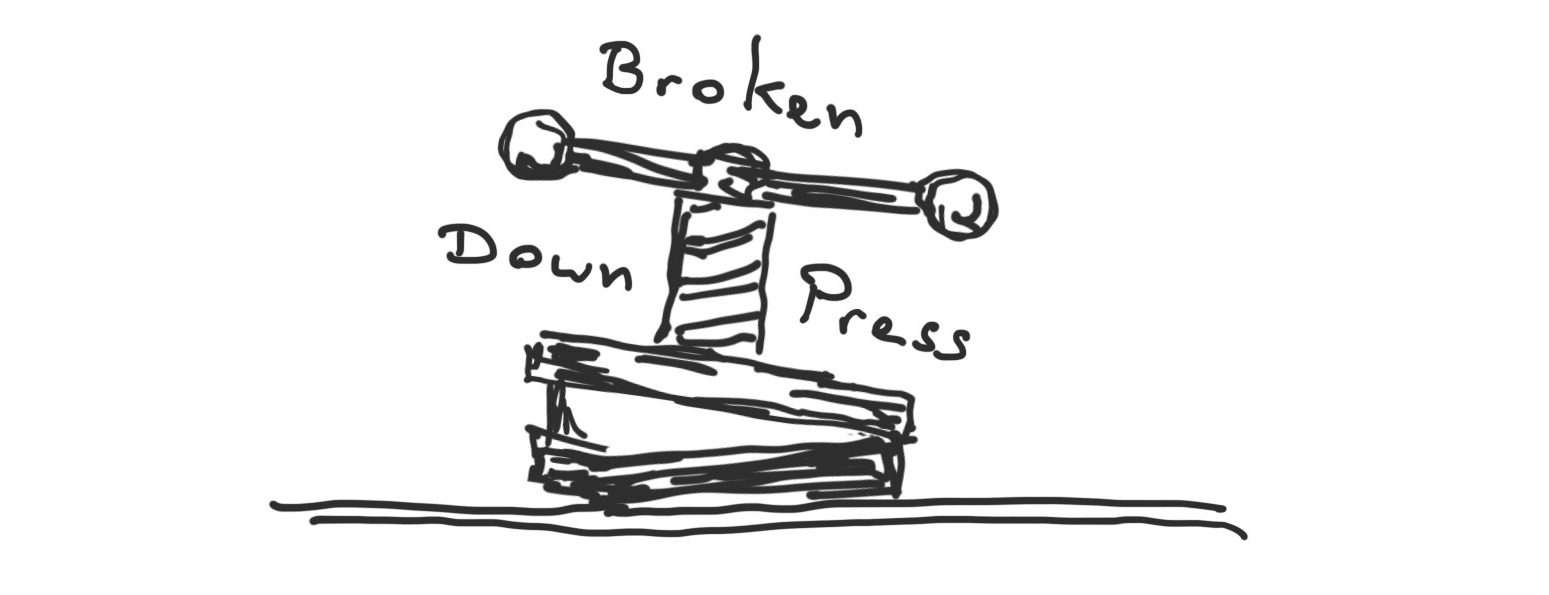

There it was. A big piece of broken wood, stuck over a wheel, swinging with the train, swinging, swinging, and with every swing rubbing against the great iron wheel of the train– SCREEE –. If it fell on the wheel it would jam it up and crash the train. If it got caught by the wheel, it could bash around like a giant club, and smash things up – break pipes and wires and struts and wood – maybe even break through the floor of the carriage. It needed pulling out and dropping down – just right, just so, onto the tracks. Malcolm Engineer looked very carefully, and thought very hard, and then he measured and checked until he was sure. He grabbed the wood, just so, and he pulled. He pulled, and he pulled, and he tugged and he pulled, but he couldn’t move the piece of wood. It was too big for a mouse alone.

He couldn’t bring a human engineer down here – the place was too small, too tight. But he knew what he could bring. He could bring a stick. A good strong stick, a pole, a lever, a walloper, to shove the wood straight off the wheel. But he had to go back, down the mouse-ways again, back to his engineers’ room.

Malcolm Engineer made his way carefully back down the mouse ways, back through the trap door, back to his room, and took up his strong, stout stick. He strapped it over his shoulder and carried it back, down along the mouse-ways again. It wasn’t easy, even for him, the stick was heavy and spoiled his balance. The train swayed and shook and bumped and rumbled, and twice Malcolm nearly fell. When he got back to the wood and the scraping wheel, he was tired. But he took out his stick, he aimed carefully, and – thunk – he jammed the stick behind the wood.

It didn’t go in.

Thunk – he tried again.

The stick slid in, between the wood and the underneath of the carriage floor.

And then he pulled.

He pulled and pulled and pulled and pulled, until, with one great last pull, the wood shifted, it moved, it started to slide. Malcolm leaped out of the way. The wood fell down. Thunk, kerblank, crash, it tumbled down onto the track, between the rails, it clumped and crashed and tumbled down, safe and clear.

Malcolm sighed. It had been a hard job – a dangerous job. He picked up his tools and his good, strong stick, and slowly, slowly, made his way back, down the mouse-ways, back to his room. In the room he set his things down, he made himself a cup of tea, he got his cookies (not the spilled ones off the floor, new ones out of the cookie jar), and sat himself down, cosy and comfy with his drink and his snack, then he stretched his toes and wiggled his whiskers, and smiled to himself.

A good job, well done.